A chess opening where a player sacrifices material, typically a pawn, to gain an advantage in development or positioning.

Introduction

A gambit in chess is a strategy where a player sacrifices material (usually a pawn, but sometimes a piece) in the opening to gain an advantage in development, activity, or attacking chances. Gambits are often used in sharp, aggressive play, but they also appear in positional chess when controlling space and initiative is more valuable than material.

What are the most famous gambits? How do you decide whether to accept or decline a gambit? And when is it best to use a gambit in your own games? This article explores the different types of gambits, key strategies, and famous examples.

1. What Is a Gambit in Chess?

A gambit occurs when a player offers material (usually a pawn) in the opening to gain:

✔ Faster piece development → Controlling the board before the opponent.

✔ Better central control → Occupying key squares for long-term activity.

✔ An attacking initiative → Gaining momentum to launch an early assault.

✅ Example of a Gambit (King’s Gambit)

- e4 e5

- f4 (White sacrifices a pawn to open the center and attack quickly).

2. Types of Gambits

2.1 True Gambit (Irrecoverable Sacrifice)

- The sacrificed material cannot be recovered, meaning the player is committed to positional compensation.

- Used in hyper-aggressive openings to gain long-term activity.

✅ Example: The King’s Gambit, where White sacrifices a pawn and doesn’t necessarily regain it.

2.2 Temporary Gambit (Recoverable Sacrifice)

- The sacrificed material can often be regained later through active play.

- Used to force weaknesses in the opponent’s position.

✅ Example: The Queen’s Gambit, where White sacrifices the c4-pawn but can often recapture it later.

2.3 Counter-Gambit

- A gambit played in response to an opponent’s move, turning the tables.

- Often leads to double-edged positions.

✅ Example: The Falkbeer Countergambit (in response to the King’s Gambit).

3. Famous Gambits and Their Strategies

3.1 King’s Gambit (1. e4 e5 2. f4)

✔ White sacrifices the f4-pawn to open lines for an early attack.

✔ Leads to sharp, attacking play, forcing Black to defend carefully.

✔ Used by Bobby Fischer, Paul Morphy, and Mikhail Tal.

✅ Accepting vs. Declining the King’s Gambit:

- Accepted (2… exf4) → Black takes the pawn and tries to defend.

- Declined (2… d5) → Black counters in the center instead of taking the bait.

3.2 Queen’s Gambit (1. d4 d5 2. c4)

✔ White offers the c4-pawn to gain central control.

✔ Unlike other gambits, White can often win back the pawn.

✔ Leads to long-term positional play, rather than all-out attack.

✅ Common Responses:

- Accepted (2… dxc4) → Black takes the pawn but risks falling behind in development.

- Declined (2… e6) → Black maintains strong central control.

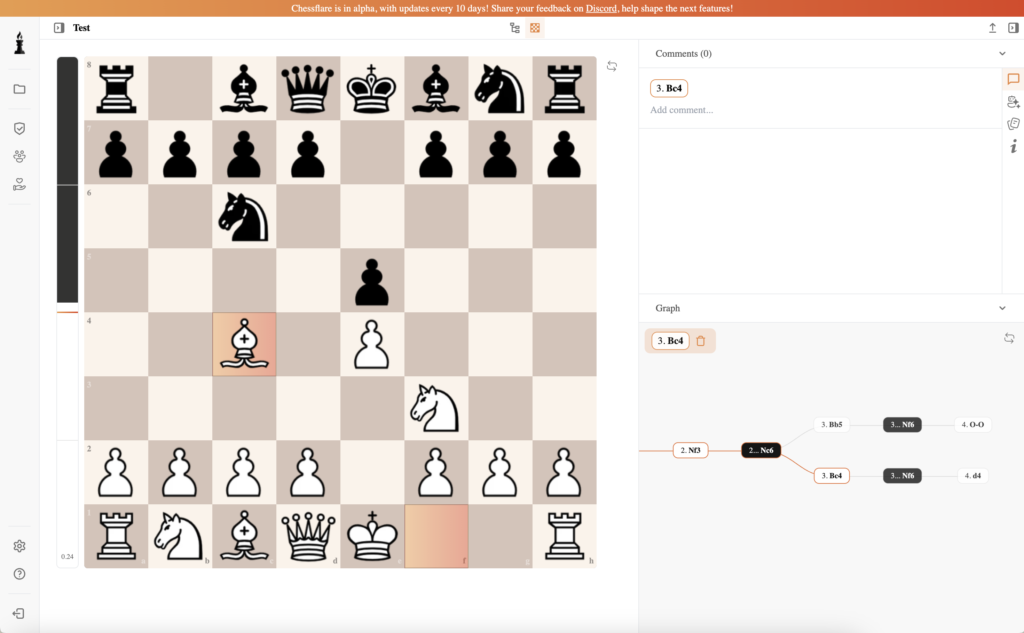

3.3 Scotch Gambit (1. e4 e5 2. d4 exd4 3. Bc4)

✔ White sacrifices a pawn to develop rapidly and attack f7.

✔ Leads to open, tactical battles.

✔ Used by Garry Kasparov in aggressive play.

3.4 Evans Gambit (1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bc4 Bc5 4. b4)

✔ White sacrifices the b4-pawn to gain tempo and attack quickly.

✔ Creates immediate threats in the Italian Game structure.

✔ Played by Paul Morphy and Garry Kasparov.

3.5 Benko Gambit (1. d4 Nf6 2. c4 c5 3. b5 a6)

✔ Black sacrifices a pawn on the queenside for long-term positional pressure.

✔ Leads to strong piece activity on the open files.

✔ A favorite of Grandmasters like Pal Benko and Garry Kasparov.

4. Should You Accept or Decline a Gambit?

4.1 When to Accept a Gambit

✔ If you can safely defend the extra material without falling behind in development.

✔ If capturing the gambit pawn weakens White’s position (e.g., Queen’s Gambit Accepted).

✅ Example: In the Benko Gambit, Black sacrifices a pawn but gains powerful counterplay.

4.2 When to Decline a Gambit

✔ If accepting would lead to an immediate attack that is hard to defend.

✔ If declining leads to solid development and central control.

✅ Example: In the King’s Gambit, Black often declines with 2… d5 to keep a strong center.

5. Common Mistakes When Playing a Gambit

❌ Overcommitting to the Attack → If your gambit doesn’t work, you’re simply down material.

❌ Ignoring Development → Many gambits fail when players sacrifice material but don’t activate their pieces.

❌ Playing Gambits Without Understanding the Ideas → Some players memorize moves but don’t know the plans behind them.

6. Famous Players Who Used Gambits

6.1 Paul Morphy

- Master of sacrificial attacks using the King’s Gambit and Evans Gambit.

6.2 Bobby Fischer

- Loved playing the King’s Gambit, but later created Fischer’s Defense against it.

6.3 Garry Kasparov

- Played Queen’s Gambit and Evans Gambit in high-level games.

7. How to Improve Your Gambit Play

✔ Practice Gambits in Blitz and Rapid Games → Gambits work well in faster time controls.

✔ Study Master Games → Learn how top players handle gambit positions.

✔ Solve Tactical Puzzles → Many gambits rely on sharp tactical play.

✔ Understand the Plans, Not Just Moves → Always ask, « What am I trying to achieve with this gambit?«

8. Conclusion

Gambits are a powerful chess weapon, offering dynamic play, fast development, and attacking chances. However, they require precise execution and tactical awareness. Whether you choose to play gambits or defend against them, understanding their principles will sharpen your game and make you a more aggressive, confident player.

✔ Use gambits to gain early activity and control.

✔ Know when to accept or decline a gambit based on positional factors.

✔ Avoid blindly sacrificing material—always have a plan!

Mastering gambits will make you a more dangerous and unpredictable opponent, giving you the ability to seize the initiative and dominate the board!